Finally, the explanation of IPR violations in China requires a look at the nation's political system. Power in China is divided between two different but inter-related entities, the government and the Chinese Communist Party. The Chinese government has executive, legislative and judicial branches, but unlike the American system there is no provision for a system of checks and balances. The judiciary, for example, is not independent and serves instead as an tool of the executive branch, which is the primary seat of power in the Government. The executive branch is comprised of 29 ministries and commissions, each with a complex bureaucracy which runs vertically from Beijing down to local levels but which also connects horizontally to provincial and local municipal governments. China's Constitution, which does not operate as a set of “fixed principles against which specific laws and practices are measured,” instead serves as a general “mission statement or policy platform.” The resulting ambiguity means that the "relationship among the central, provincial, and local governments is thrashed out in case-by-case agreements that are subject to renegotiations as conditions and needs change.”[1]

Further complicating the system is the Chinese Communist Party, a member of which is appointed at each node in the government matrix to ensure the Party's prerogatives are carried out and to maintain its power in the system.

These are the basics of the Chinese political system, a system which has had to manage and allocate unprecedented amounts of wealth since Deng's reforms began; a system in which ad hoc bargaining and the reciprocation of favors have created countless bonds of loyalties which thwart the implementation of national laws; and a system where the rule of law and an independent judiciary have not created the wide, institutionalized networks of trust that lubricate economic transactions and ensure legal protection for innovation, creativity, and invention. As Dr. Jean Oi of Stanford University stated, “Corruption is a big problem, but not the defining characteristic of the system. The problems stem from institutional structure.”[2] And the reform of this structure stands as one of China's most pressing needs as it proudly resumes its place among the world's great economic powers.

The End

Notes:

[1] Starr, Understanding China, p. 56.

[2] From a lecture Dr. Oi gave to the Fulbright Hays 2007 History and

Culture delegation to China, June 26, 2007.

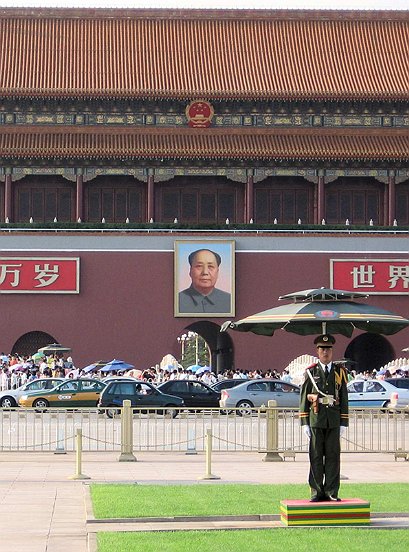

Although most youth today are indifferent to Mao, his portrait in Tiananmen Square is a reminder of the Communist Party's power within the Chinese political system.

EMAIL the author